Intermediate to Advanced TypeScript

Write better code and understand TypeScript at a deeper level.

Stick around, let's learn some good stuff! 🔥

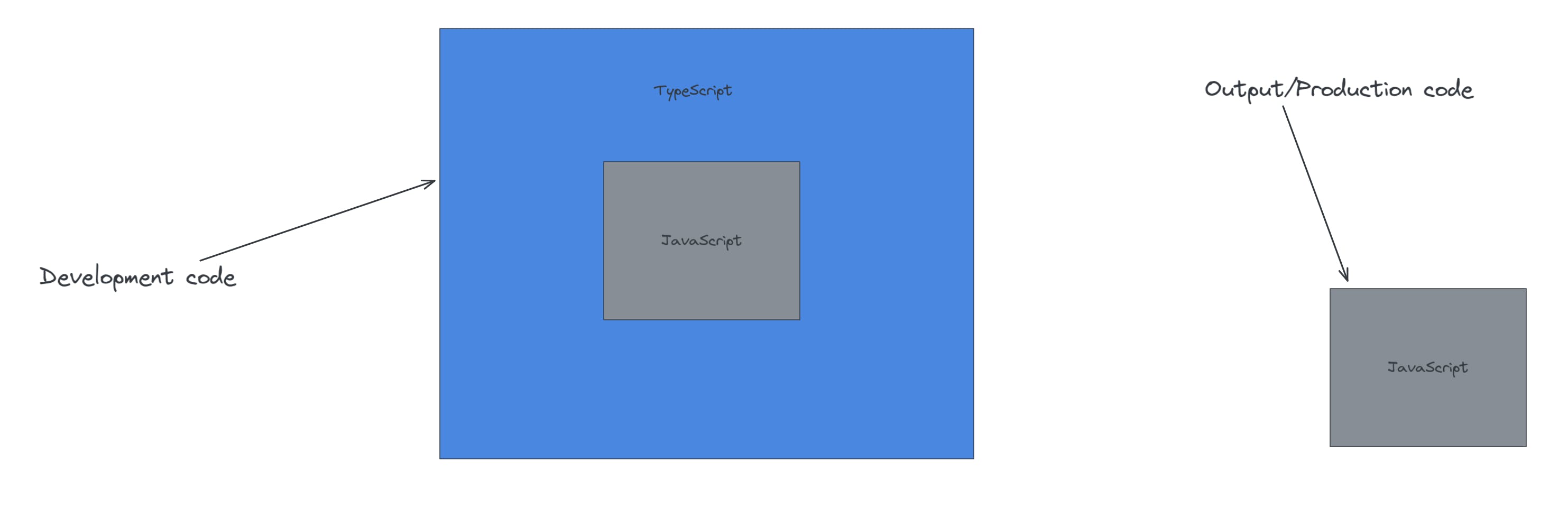

Superset of JavaScript

TypeScript is a programming language that builds on top of JavaScript to help with development during compile-time.

TypeScript isn't the code that runs during runtime (the output), it compiles down to JavaScript in the end, and that is what actually runs when you run the software.

This means for instance that any JavaScript code is valid TypeScript code, but this also means that you can't rely on TypeScript 100%. It can't guarantee the types that run during runtime, meaning it is good to also check your types/schemas were necessary during runtime as well (using Zod for example).

Type Inference

TypeScript can infer a lot of types by default. This means you should type when necessary, but you should avoid it when you don't have to

This is one of the things that makes TypeScript smart, it is there to help you, not being a burden.

let isOk: boolean = false;

isOk = true;

Above, it isn't necessary for us to type isOk as a boolean, TypeScript already knows it because we're setting the value to false, hence it can infer that the variable should be a boolean.

/*

* The type will still be a boolean.

* TypeScript infers that it's a boolean

* because we're setting the value to false

*/

let isOk = false;

isOk = true;

Type Inference works in many places, so strive to infer more types when it makes sense, as it is generally more productive.

Let's look at another example:

/*

* The return type will be a string,

* TypeScript is smart enough to understand whatever a

* function returns or could be returning.

*/

function returnString(str: string) {

return str;

}

returnString("hello");

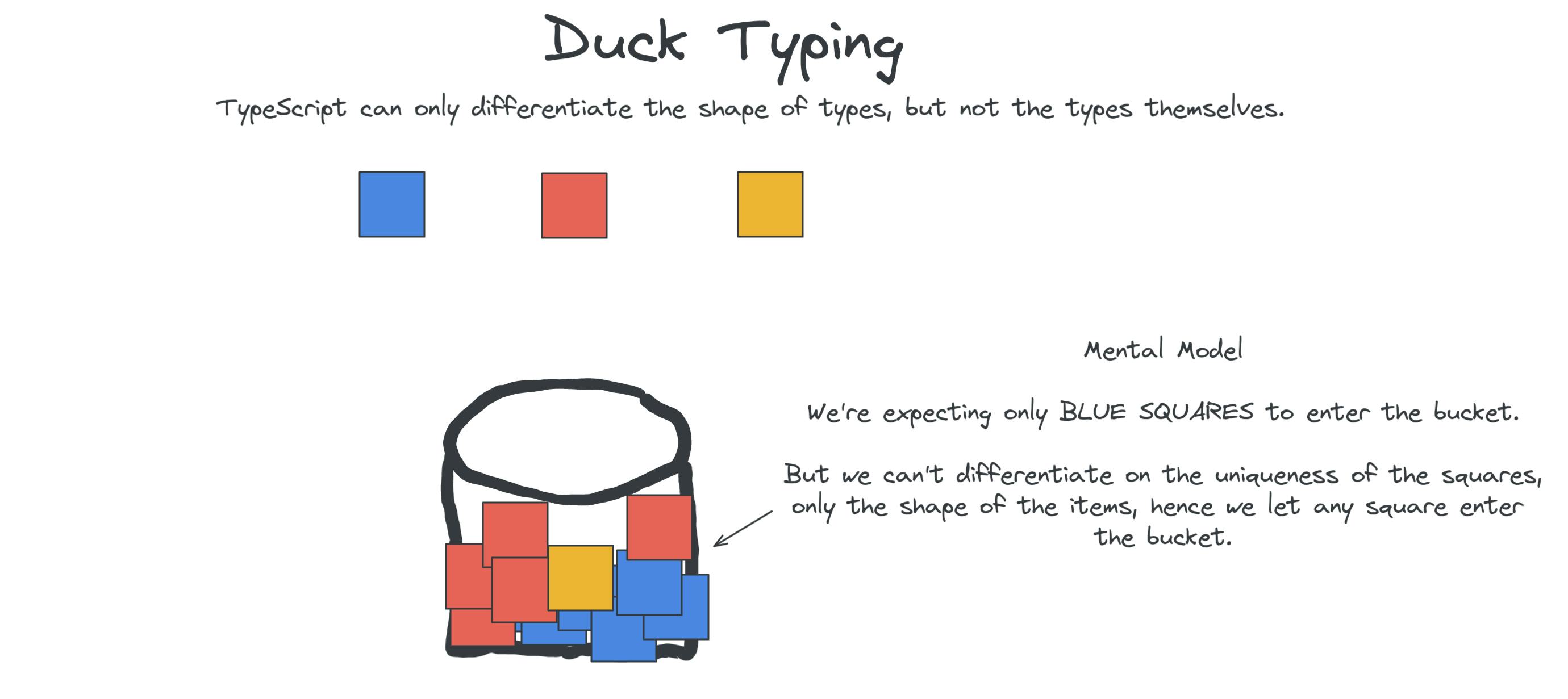

Types are not unique (Duck Typing)

Each type isn't unique like in some other programming languages. TypeScript just cares about the structure of the type that you give a variable when trying to match the structure to a specific type.

This of course could be better, but regardless, the experience of writing TypeScript is better than writing pure JavaScript considering the benefits of type-checking.

Let's take a deeper look at some code to fully grasp this:

type Fish = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

type Animal = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

const animal: Animal = {

name: "junior",

age: 12,

};

function logFish(fish: Fish) {

console.log(fish);

}

/*

* This doesn't throw an error because the structure of `animal` fulfills

* the structure of the type `Fish`, even though they are of different types,

* TypeScript just cares about the structure and not the uniqueness of

* the types themselves.

*/

logFish(animal);

In some other programming languages, the compiler wouldn't allow the above example to go through, since types are unique.

type Fish = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

const animal = {

name: "junior",

age: 12,

hello: "uhm this should make log fish function not work uhm",

};

function logFish(fish: Fish) {

console.log(fish);

}

//

/*

* This doesn't throw an error because the structure of `animal`

* fulfills the structure of the type `Fish`, even though it adds

* another property, TypeScript just cares that you suffice the structure.

*/

logFish(animal);

You could probably create more examples here, but this is just one which shows that TypeScript is quirky and not 100% reliable despite how good it is. To prevent this, we could type animal to be Fish:

const animal: Fish = {

name: "junior",

age: 12,

// TypeScript will yell here. Because this type must have exactly the same structure as the Fish type.

hello: "uhm this should make log fish function not work uhm",

};

Avoid type assertions

Avoid type assertions. While it does give a type, it also silences the compiler. This will break your type checking

There are complicated cases where you may want to use them. If type assertion is being used, it is either because it was absolutely necessary or it is a code smell and code that should be refactored.

Let's take a look at some code to grasp this.

type Human = {

name: string;

arms: number;

};

const human = {

name: "Dora",

// Does not throw an error, even though `arms` is a required property.

} as Human;

A better way to type this in order to get TypeScript yelling at you:

type Human = {

name: string;

arms: number;

};

// TypeScript will yell here that `arms` is a missing property since it is required in type `Human`.

const human: Human = {

name: "Dora",

};

A case where you may want to use type assertion because TypeScript can't know the type is when fetching:

type Human = {

legs: number;

name: string;

age: number;

};

const response = await fetch("....");

// If we don't typecast the data here, it will have `any` as a type.

const data = (await response.json()) as Human;

To be completely honest with you, a better scenario for the above code is to check the structure of the data at runtime and make sure it matches a schema. You could achieve this for an instance by using the famous library Zod.

Avoid any type

Avoid using the any type. You literally lose the whole point of TypeScript by doing so:

- Autocompletion

- Type checking

It is extremely bad. It increases the cognitive effort working with the code significantly.

There are specific use cases where you're forced to use any, but those are out of the scope of this blog post.

Template Literal Types

I think this is one of TypeScript's cool features, when I saw it, I started using it right away in so many places.

It is quite simple to understand, we can narrow the string type, to not just a union type, but literally the string values themselves in detail.

Let's say we want to have a type for an email:

type Email = string;

Emails will be strings, so this makes sense, but are there any ways we can narrow this type? For an instance, what if we only want a type for Gmail addresses?

Yes, we can.

// Type of email is: `${string}@gmail.com`.

type Email = `${string}@gmail.com`;

Now, this is sick. You can already imagine how far we can take it.

What if we just don't want .com addresses?

type Domains = "com" | "de" | "net";

// Type of email is: `${string}@gmail.com` | `${string}@gmail.de` | `${string}@gmail.net`.

type Email = `${string}@gmail.${Domains}`;

We can take this really far, this is one of my favorite features with TypeScript, it really lets you narrow down the string types, enhancing the type safety and better development experience.

Feel free to play around with Template Literal Types over at Playground.

Type narrowing

If we don't know the shape or type of a value because it can be multiple ones, we have to narrow down the type so Typescript doesn't yell at us.

function logWithMetadata(value: number | string) {

if (typeof value === "number") {

// This will be a number.

console.log("number", value);

} else {

// This will be a string.

console.log("string", value);

}

}

Another example with objects.

type Animal = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

type Human = {

name: string;

arms: number;

};

function logWithMetadata(value: Human | Animal) {

if ("arms" in value) {

// This will be a Human.

console.log("human", value);

} else {

// This will be an Animal.

console.log("animal", value);

}

}

Discriminated Unions

A pattern in TypeScript is to have a property that serves as a distinguisher to determine what type a value is of.

type Animal = {

name: string;

prey: string;

sleepHours: number;

// We use this to check if a value is an animal.

type: "animal";

};

type Human = {

name: string;

age: number;

// We use this to check if a value is a human.

type: "human";

};

type Ghost = {

name: string;

color: string;

// We use this to check if a value is a ghost.

type: "ghost";

};

type Creature = Animal | Human | Ghost;

function logWithMetadata(value: Creature) {

if (value.type === "animal") {

// This is an animal. We can log `prey` and `sleepHours` here.

console.log("animal", value.prey, value.sleepHours);

} else if (value.type === "ghost") {

// This is a ghost. We can log `color` here.

console.log("ghost", value.color);

} else {

// This is a human. We can log `age` here.

console.log("human", value.age);

}

}

Unknown over any

Use the unknown type over any.

Like any, any value can be assigned to unknown; however, unlike any, you cannot access any properties on values with the type unknown, nor can you call/construct them, to do so you'd have to narrow down and help TypeScript detect what shape a variable has.

const variableAny: any = 10; // We can assign anything to any

const variableUnknown: unknown = 10; // We can assign anything to unknown just like any

const s1: string = variableAny; // Any is assignable to anything

const s2: string = variableUnknown; // Invalid; we can't assign unknown to any other type

variableAny.method(); // This is fine.

variableUnknown.method(); // This isn't fine, TypeScript wants to know the shape first.

Unknown tells TypeScript: We don't know the shape of this variable, but before using it, we should first know it.

Let's take a look at how we can narrow down the type to properly use the values:

function stringify(value: unknown): string {

if (typeof value === "function") {

// Within this block, `value` has type `Function`,

// so we can access the function's `name` property

const functionName = value.name;

return `function name: ${functionName}`;

}

if (value instanceof Date) {

// Within this block, `value` has type `Date`,

// so we can call the `toISOString` method which exists on it

return value.toISOString();

}

return String(value);

}

Be aware of enums

You should strongly be aware of enums.

- They aren't as type-safe as you think, unions are better options when possible.

- It is better to use an object if a union doesn't fit the case because it keeps your codebase aligned with the state of JavaScript.

TypeScript documentation: Objects vs Enums.

Related article: Prefer union types over enums.

I could go in-depth in this article, but I think existing resources already explain it perfectly.

There is an Eslint rule for that as well, avoiding enums, you can set it to warn.

{

"rules": {

"no-restricted-syntax": [

"warn",

{

"selector": "TSEnumDeclaration",

"message": "Don't declare enums"

}

],

},

}

Use Array for arrays

This is subjective but stick to Array when annotating the type of arrays to enhance readability and be consistent with a single way of typing arrays.

Examples:

User[]->Array<User>(string | number)[], ->Array<string | number>string[], ->Array<string>

There is an Eslint rule for this:

{

"rules": {

"@typescript-eslint/array-type": ["error", { "default": "generic" }],

},

}

Boolean variables

This is subjective, but be consistent with the naming of boolean variables.

Make sure they have prefixes to indicate they are boolean variables for readability & consistency purposes.

Recommended prefixes:

- is

- should

- has

- are

- can

There is an Eslint rule for this:

{

"rules": {

"@typescript-eslint/naming-convention": [

"warn",

{

"selector": "variable",

"types": ["boolean"],

"format": ["PascalCase"],

"prefix": ["is", "should", "has", "are", "can"]

}

],

},

}

Avoid function overloading

Avoid overloading functions, declaring multiple types for a function since it will be used differently depending on the arguments you pass to it.

Why:

- Functions having multiple responsibilities

- More cognitive effort to understand "what" the function is doing

This breaks the single-responsibility principle and causes more pain than it actually helps.

It is best if you've multiple different functionalities to split it into multiple functions.

There is an Eslint rule for this:

{

"rules": {

"@typescript-eslint/no-redeclare": "error",

},

}

The above lint rule will make sure you're not declaring a type or variable with the same name in the same file.

Generics

Generics are placeholders for types. They should be used when the parameters of a function, properties of a type or interface, or class properties can be of multiple types or you don't know the shape of the type.

Let's say we have a function that returns the parameter right away, but we don't know the shape or type of the parameter.

One option is to use the any type:

function returnParam(param: any) {

return param;

}

/*

* The problem here is that `a` has `any` type,

* even though that should be string, and it

* doesn't matter what we pass as an argument.

*/

const a = returnParam("hello");

The problem here is that we lose the type-safety and of course any should be avoided for that reason.

Let's take a look at using a generic for the type.

function returnParam<Type>(param: Type) {

return param;

}

/*

* The type of `a` is "hello".

* This is because we're using a `const`, hence TypeScript notices that,

* and turns this into a constant that can only have the value "hello".

*/

const a = returnParam("hello");

You may have noticed, that we didn't pass the generic as an argument, which I will show you soon, but this is also one of the cool things with TypeScript, when possible, it can infer the type of the generic!

function returnParam<Type>(param: Type) {

return param;

}

/*

* This is the same as the previous code block,

* but here we are explicitly passing a generic to

* the `returnParam` function. This is how it was behaving

* in the previous code block.

*/

const a = returnParam<"hello">("hello");

What if we want to use a let so we can reassign the variable in the future?

function returnParam<Type>(param: Type) {

return param;

}

/*

* `a` will now be of type `string`, since

* we've explicitly passed `string` as the generic.

*/

let a = returnParam<string>("hello");

Here is something cool, we don't need the string generic, TypeScript will know that this can be reassigned due to the let keyword and understand that its type should be a string.

function returnParam<Type>(param: Type) {

return param;

}

/*

* `a` is still of type `string` since TypeScript

* understands due to `let` that this variable may be reassigned

* in the future, hence it isn't stupid to keep the type too strict.

*/

let a = returnParam("hello");

Think of generics like function arguments, if that mental model helps.

Multiple generics

We can also pass multiple generics as types.

function returnParam<FirstType, SecondType>(

firstParam: FirstType,

secondParam: SecondType

) {

return { firstParam, secondParam };

}

/*

* Both properties inside `obj` have the type string.

* TypeScript knows that you can't reassign objects,

* but you can update their properties in JavaScript, despite using `const`.

*/

const obj = returnParam("hello", "uhm");

Try not to pass the generic unless it's necessary, TypeScript can infer a lot.

We can of course have as many generics as we want.

Extends

What if we want the generic to be of a certain structure? That is when the extends keyword comes into play. With extends we can tell TypeScript: This generic must be of this structure.

Look at how I'm saying structure here because as previously mentioned in this article, types aren't unique in TypeScript.

type Fish = {

name: string;

color: number;

};

type Lion = {

name: string;

weight: number;

};

type Bird = {

color: string;

name: string;

wings: number;

};

type Animal = Fish | Lion | Bird;

type Human = {

name: string;

country: string;

};

type Creature = Human | Animal;

/*

* Here we're passing two generics, one who has to be of type `Animal`

* and the other of type `Creature`. We can set this contract through

* the `extends` keyword.

*/

function getNames<AnimalType extends Animal, CreatureType extends Creature>(

animal: AnimalType,

creature: CreatureType

) {

return [animal.name, creature.name];

}

const lion: Lion = {

name: "Simba",

weight: 4335,

};

const human: Human = {

name: "Tiger",

country: "Germany",

};

// `names` is of type `string[]`, an array of strings.

const names = getNames(lion, human);

It is always good in TypeScript, whenever possible, to narrow down your types. This will take full advantage of type safety. In our case above, we are using the extends keyword, but another example of narrowing could be to use a union type whenever possible, rather than just a string type.

You can give your generics default types, this is good when you know your generic will oftentimes be of a certain type, but you don't always want to pass it (if TypeScript forces you to).

Think of it like giving parameters default values.

/*

* Here we default the generic `AnimalType` to be type `Fish`.

* This is possible because `Fish` is a part of the `Animal` type.

*/

function getName<AnimalType extends Animal = Fish>(animal: AnimalType) {

return animal.name;

}

Conditional types

extends keyword allows us to also write conditional types. We can determine what type a generic should have, depending on the structure of the value passed.

Conditional types can be read as ternary operations in JavaScript.

type Fish = {

name: string;

color: number;

};

type Lion = {

name: string;

weight: number;

};

type Animal = Fish | Lion;

type Human = {

name: string;

country: string;

};

type Creature = Human | Animal;

/*

* This can be read as a ternary operation.

* If the `Type` generic is of type `Human` then `Creature`

* will be returned as a type, otherwise `Animal.`

*/

type Conditional<Type> = Type extends Human ? Creature : Animal;

You could read the Conditional as: const conditional = type === human ? creature : animal.

Where ever you are able to use extends you can create conditional types.

Read more about conditional types: Conditional Types.

Type Distribution

Type distribution is out of the scope of this blog post, but I recommend this article if you're interested in it: Complete guide to type distribution in TypeScript.

Infer

Let's talk about the infamous infer keyword. It gained infamy because it is extremely hard to understand and grasp. It took me ages to understand it, I won't lie.

I hope to explain it in a way that you too understand, forgive me if I don't.

There are times in TypeScript when we are not sure how the shape will look because it might get changed. What we can do in such scenarios is to store the type we want in a variable using infer and return that.

Let's say for example we want to get the return type of a function, any function. We want a type looking like this:

type TypeOfReturn = ReturnTypeOfFunction<Fun>;

Let's write the type ReturnTypeOfFunction together.

Let's start off with a function that just returns the type of the function to warm up.

type ReturnTypeOfFunction<Fun> = Fun extends (...args: any[]) => any

? Fun

: never;

type GetPostFunction = ReturnTypeOfFunction<typeof getPost>;

Above we get the type of getPost and store it in GetPostFunction, this is completely unnecessary since we can just do typeof getPost to get the type, but bear with me, we're just using this as a learning example.

Let's complete the function to return the type of whatever the function returns.

// `any` gets replaced with a variable that returns the actual type.

type ReturnTypeOfFunction<Fun> = Fun extends (...args: any[]) => infer Return

? Return

: never;

type PostType = ReturnTypeOfFunction<typeof getPost>;

In ReturnTypeOfFunction the any return type got replaced with infer Return, we can then use Return which contains the actual type that TypeScript infers, and return it from the conditional type whenever it passes. It will pass as long as you pass in a function.

This can be a bit tricky to understand because we didn't really get rid of whatever was in the position of any, we replaced it with something to dynamically infer the type.

This part confused me the most about infer, where did the other variable go (any in our case), but we just replaced that part by storing the type in a variable whose type we can return.

I know I'm repeating myself, but this is one of the hardest things to grasp in TypeScript.

We won't know the return type inside ReturnTypeOfFunction, but we will know it when we're using it.

type PostType = ReturnTypeOfFunction<typeof getPost>;

type UserType = ReturnTypeOfFunction<typeof getUser>;

type FoodType = ReturnTypeOfFunction<typeof getFood>;

Above are a few more examples, showcasing how we can use this for multiple functions.

By the way, the type we wrote, there is already a built-in utility type for this called ReturnType in TypeScript.

Conclusion

I hope this helped, and took your TypeScript understanding & knowledge a step higher. TypeScript is different from other typed languages out there, primarily because it is a superset of JavaScript, but it is phenomenal that it exists. After writing TypeScript, I can never go back to just writing pure JavaScript.